"UTTARAYANA PUNYA KALAM"-MAKAR SANKRANTHI IN TELUGU STATES

The cultural landscape of India is remarkably distinctive. Our festivals articulate the essence of our culture, encompassing our customs and traditions. Festivals serve as moments of respite for individuals weary from the relentless pursuit of existence, guiding their reflections towards the transcendent. The design of our festivals reflects the profound relationship between humanity and the natural world, exemplified by the Sankranthi Festival. “San” signifies something exceptional and remarkable, while “Kranthi” denotes a time of prosperity—Sankranthi represents a festival that bestows significant abundance. Saturn governs Capricorn, signifying that when the Sun transitions into Makara Rasi, it embarks on a visit to its progenitor, Saturn. In the Mahabharata, Bhishma Pitha reclined upon a bed of arrows, patiently awaiting the arrival of “UTTARAYANA” to transition from this realm, having been endowed with the ability of Iccha maran (the power to summon death at will) by his father. With the arrival of Sankranthi, the auspicious period of Uttaranaya Punya Kalam commences. Uttarayana Punyakalam encompasses the initial half of the year, spanning from mid-January to mid-July. From mid-July to mid-January, this period is referred to as “DAKSHINAYANA PUNYAKALAM.” Within the puranas, one can uncover remarkable narratives associated with Makar Sankranthi. In a general sense, Uttarayanam is allocated for the veneration of the Lords and Deities, while Dakshinayana is dedicated to the observance and expression of gratitude towards our ancestors. By segmenting the sun's trajectory into two distinct phases, one can discern that the equatorial line, which bifurcates the northern and southern hemispheres, is aligned with Uttaranaya, a period when the sun's movement inclines towards the north. Conversely, during Dakshinayana, the sun is observed to be positioned south of the equator, indicating its tilt towards the south. During Uttarayana, the duration of daylight extends, whereas in Dakshinayana, the length of night prevails. A text from 2000 years ago by Varahamihira references the works of Bhaskaracharya, specifically the Siddhanta Shiromani, which is 1600 years old. This work elucidates the concept of Sankranthi, the movement of the sun, and the resultant changes or effects with remarkable clarity. Numerous transformations take place in the natural world; shadows recede, and illumination is disseminated. In the period of Dakshinayana, human digestive capacity diminishes significantly, resulting in an extended duration for the digestion of consumed food. Issues related to indigestion are frequently observed alongside ailments such as cough, cold, and influenza. Humans and cattle experience an increase in bacterial and viral assaults during the period of Dakshinayana. In light of this understanding, during Dakshinayana, it is advised by elders to refrain from consuming oily foods and instead to opt for simple, easily digestible meals. During Dakshinayan, the practice of “Shakthi Aaradana” becomes increasingly prominent as a means to harness energy. Uttaranaya is greeted with an array of snacks and culinary delights, often prepared or fried in oil. Arisalau, murukulu, managapoovuly, sesame ladoos, and cakes. A diverse array of culinary establishments, offering both confections and savoury dishes, are crafted from flour, as the digestive capacity of humans and other organisms is notably heightened during the period of Uttarayana. Consequently, certain guidelines and types of dietary consumption to be observed during Uttarayana are also delineated. Given the elevated temperatures of the Sun, lentils, commonly referred to as pulses, alongside rice, which are currently being harvested, are combined with jaggery to prepare PONGAL, a dish that is consumed following a ritual of reverence towards the Sun. Within each of our festivals lies an underlying scientific perspective, revealing a deeper understanding of the world around us. Makar Sankranthi is referred to by various names throughout the nation, and in the Telugu-speaking regions, it is known as “Pedda Panduga”—a significant celebration or Sankranthi. This festival spans three days, with the inaugural day designated as “Bhogi.” Bhogi is observed with great enthusiasm in the villages, and it is noted that on the day of Bhogi, Sri Andal from Sri Villiputur made her entrance to Sri Rangam and merged herself with Sri Ranganathaswamy.

A fire is kindled before the residences, consuming an array of antiquated items—rags, garments, bedding, carpets, and various sticks, among others—reduced to ashes in its flames. In undertaking this endeavour, one aims to eliminate the accumulated detritus from the residence, thereby creating room for new acquisitions, while simultaneously ensuring that any pathogens and microorganisms associated with the discarded items are incinerated in the process. Subsequently, the floors, roofs, and walls of the house undergo a thorough washing and cleaning, after which everyone partakes in a head bath and adorns themselves in fresh attire. Sesame ladoos and cakes are provided for consumption. To enhance the well-being of young children, toddlers are encouraged to consume indigenous berries known as Regu Pallum, which serve as a significant source of vitamin ‘C’ and are accessible during this season through the practice of ‘Bhogi Pallum’. In the rural expanse of Andhra Pradesh, one can observe bullfights and rooster fights at virtually every turn. In Telangana, the art of kite flying manifests itself, adorning the sky with a diverse array of vibrant kites. In rural locales, the front and back courtyards are treated with a mixture of liquid cow dung, resulting in a polished and even surface. This functions as a disinfectant while simultaneously maintaining a cooler ground temperature. From the onset of Dhanur masam until Sankranthi, the streets are adorned with vibrant rangolis, particularly featuring the intricate chariot design. Chariot rangoli is meticulously crafted even on the primary thoroughfares and throughout the urban landscape. The powder employed in the creation of rangolis is abundant in calcium, effectively deterring microorganisms from the streets and preventing their intrusion into homes. Additionally, certain individuals utilise rice flour to create rangolis, which serve as sustenance for ants and other insects, thereby deterring them from intruding indoors. Moreover, women engage in the practice of creating rangolis, which serves as a form of exercise beneficial for the waist and addresses various uterus-related concerns and ailments.

The second day marks the occasion of Sankranthi. One observes the arrangement of “Gubbillu”—cow dung moulded into a conical shape and positioned at the centre of the rangoli moggu, adorned with indigenous flowers such as Gummidi (ash gourds), Bera (ridge gourds), and Potla (snake gourds), complemented by Chemanthi and strands of “Gariga” grass, and embellished with turmeric and vermillion powders. Women congregate in groups, engaging in song and celebration. In Andhra, it is referred to as “Gobbemma,” whereas in Telangana, it is known as “Gonthemma.” The act of engaging in circular movements while vocalising melodies and celebrating is referred to as “Gobbillatta.” The Gobbemma serves as a profound emblem of the essence of nature, encapsulating melodies that celebrate the natural world, femininity, and the divine narratives of Krishna, with a palpable sense of joy manifesting in its vibrant expression. Shri Annamacharya's compositions are articulated as follows: “Kolani doppidiki Gobbilo, Yadukula swamiki gobbillo.”.

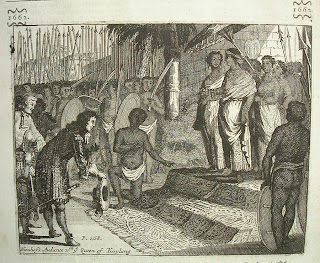

At this juncture, one can observe the presence of “Haridasarus” and “Gangi reddlu” traversing the streets, visiting each household to perform the sacred melodies of hari ganamrutama while graciously receiving alms.

In the evening, one can take pleasure in the cattle race, which once more symbolises the principles of robust cattle breeding, reflecting a lifestyle of vitality and a thriving community. On the third day, “Kanuma.” The livestock that contribute to agricultural practices are meticulously cleaned, and their horns are adorned with paint and embellished with decorative bells and pompoms specifically crafted for them. Affluent landlords and proprietors bestow sarees and dhothis upon their workers as a gesture of affection and recognition.

Comments